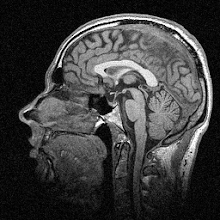

The premise of the paper harks back to my earlier post on visual dominance and multisensory integration. It’s been well known in the literature for a while that if you flash a couple of lights while at the same time playing auditory beeps, an interesting little illusion occurs. If participants are asked to count the number of flashes, and they’re the same as the number of beeps, then they almost always get the answer right. But if there are two flashes and one beep, or one flash and two beeps, then they’re much more likely to say there was one or two flashes respectively. The figure below (Figure 1 in the paper) illustrates this:

Illusion when the hand is at rest

In the figure, you can see that the bar for one beep and one flash (far left black bar) and two beeps and two flashes (far right white bar) are at heights 1 and 2 respectively, which illustrates the number of perceived flashes. That is, the number of perceived flashes is just what you’d expect – one for one flash, two for two flashes. However the middle bars, which show the one beep/two flash and two beep/one flash conditions, are at intermediate heights, showing the presence of the illusion. This figure actually demonstrates the first problem with the paper, which is that the figures are pretty difficult to interpret. I know I wasn’t alone in the lab at finding them confusing anyway.

What the authors were interested in is whether a goal-directed movement could alter visual processing, and they used the illusion to probe this. Participants had to make point-to-point reaches from a start point to a target. During the reach their susceptibility to the illusion was tested at the target point – but the test began a variable time away from the start of the movement, between 0 and 250 ms. That is: sometimes the flashes and beeps occurred at the start of the movement when the arm was moving slowly, sometimes when it was half way through and thus moving faster, and sometimes at the end when it was moving slowly again.

The experimenters found that, when there were two flashes and one beep, participants were less likely to see an illusion during the middle part of their movement than during the beginning and end. That is, they were more likely to get it right when they were moving faster. The trouble starts when you look a bit closer at the effect they’ve got – it’s pretty weak. There seems to be a lot of noise in the data, and the impression that they’re grasping at straws a little isn’t helped by the aforementioned sloppy figures.

Having said that, the stats do hold up. What might be the explanation for this kind of effect? The multisensory integration argument is that the sensory modality (e.g. vision) with the least noise should be the one that is prioritized. So when the arm is moving quickly, there’s more noise in the motor system compared with the visual system and thus you’re better at determining how many flashes there are. I’m not sure I buy this; the illusion is about the visual and auditory systems, after all. I’m not sure I get why you’d be better at detecting an illusion when you’re moving than when you’re not moving, for example. The authors claim that the limb movement “requires extensive use of visual information” but again I’m not so sure. When we reach for objects we generally take note of where our arm is, look at the object and then move the arm to the object without looking at it again.

So, a weak effect that isn’t well explained. That wouldn’t be so bad, but the clarity of the paper is also lacking. There’s also the question of why, if they had such a weak effect, they didn’t do another experiment or two to tease out what was really going on. I do think the slightly larger problem here is the review process at PLoS. It’s open access so anyone can read it free online, which I am very much in favour of, but it’s biased towards only reviewing the methods and results of a paper rather than the introduction/discussion. I go back and forth over whether this is a good thing. Some journals reject papers based on novelty (a.k.a. coolness) whereas it appears that PLoS strives to accept well-performed science regardless of how ‘interesting’ (and I use the term in quotes advisedly) the result is.

In this case I think that, while the science is good, it would be a much better paper if it went a bit more into depth with a couple of extra experiments exploring these effects more carefully – and if it had figures that were perhaps a bit easier to comprehend.

--

Tremblay L, & Nguyen T (2010). Real-time decreased sensitivity to an audio-visual illusion during goal-directed reaching. PloS one, 5 (1) PMID: 20126451

Image copyright © 2010 Tremblay & Nguyen

No comments:

Post a Comment